Grind For Yellow - Distance to Different

Solved: ✅

Difficulty: ★★★★☆☆

Uniqueness: ★★☆☆☆☆

Problem Statement

Once again, for those willing to give the problem a try, you can find the problem here. For those that don’t want to click away, here’s the problem statement:

Consider an array $a$ of $N$ integers, where $1\leq a_i \leq K $ and every integer $\in [1,K]$ appears at least once. Consider array b, where $b_i$ is the distance between $a_i$ and the closest element not equal to $a_i$, or simply $b_i = \underset{j \in [1,N], a_i \neq a_j}{\min} |i - j|$.

Calculate the number of different arrays $b$ if we consider all possible $a$ (modulo 998244353).

Intuition

Another counting problem…

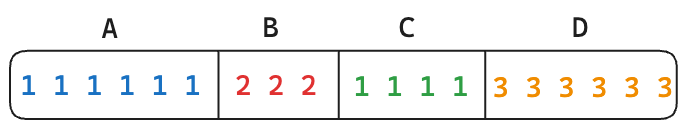

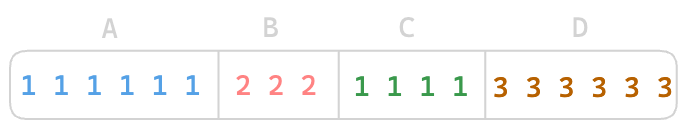

Initially, this seems somewhat straightforward. Notice, we can partition array $a$ into blocks of equal elements.

Partition of Array $a$ into Blocks of Equal Elements

Partition of Array $a$ into Blocks of Equal Elements

This is an intuitive approach as the distance of every element depends only on the neighboring blocks. For instance, all $b_i$ corresponding to block B only depend only on block A’s and block C’s distance from it. More importantly, the values $b_i$ is fully determined when the partitions of $a$ are decided.

Another important observation is that it does not depend on what elements are in the block. For example, block C could have easily been replaced by 4s, resulting in the same $b$. This implies that we only require the number of partitions to be $\geq K$, as there exists some array $a$ in which every integer $\in [1,K]$ appears at least once and can be partitioned in the same way.

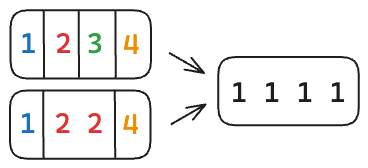

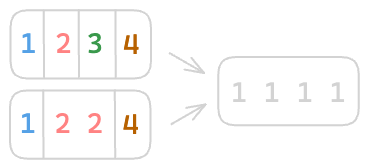

So we’re done? Calculate the number of ways we can partition the array into at least $K$ blocks? Unfortunately, there is still more to be done. Although each possible $b$ must correspond to some partition, there may be multiple different partitions that can generate the same $b$. In other words, the relationship is not bijective.

2 Different Partitions of Array $a$ with Same Resulting $b$

2 Different Partitions of Array $a$ with Same Resulting $b$

How can we avoid such double-counting?

Solution

The key is to notice that only blocks of length 2 between two other blocks are susceptible to double-counting (by splitting them into 1-1 blocks). We know the blocks at the ends cannot be double-counted by splitting, as it will affect the value of $b_i$ at the corresponding end.

For all other block lengths $l \geq 3$ in between two blocks, we can prove that no double counting can occur through splitting. For all $l \geq 3$, we know the center element(s) is $\lceil{\frac{l}{2}}\rceil$, which $\geq 2$. Notice, any split must cause this center value to change.

Simply put, if we do not consider all partitions where there exists a block of length 2 in between 2 blocks, we obtain a bijection between the number of partitions of $a$ and the resulting $b$.

Next, to calculate this, we can keep track of the number of unique partitions that does not include a block of length 2 in between other blocks through Dynamic Programming (DP). Let $dp_{i,j,k}$ represent such partitions only considering $a_1$ to $a_{i+1}$ that has $j+1$ blocks in total where the $a_{i+1}$ is $k$ distance away from the previous partition (0 if none). The transition is shown below:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eq:dp-transition} dp_{i,j,k} = \begin{cases} \underset{k'\neq 2}{\sum}dp_{i-1,j-1,k'}& if\ k = 1 \\ dp_{i-1,j,k-1}& otherwise \\ \end{cases} \end{equation}\]This however is $O(N^3)$. However, we just have to notice ultimately we only care whether we have $\geq K$ blocks and whether the distance away from the previous partition is $> 2$ and that those cases are treated equally. Hence we can modify our state a little, i.e. when $j = K-1$, $dp_{i,j,k}$ keeps track of those partitions that has $\geq K$ blocks. Similarly, when $k = 3$, $dp_{i,j,k}$ keeps track of those partitions where the distance from the previous partition $\geq 3$. This reduces the number of states to $O(NK)$, thus solving the problem.

Code

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void fast_io() {

ios_base::sync_with_stdio(0);

cin.tie(nullptr);

}

// Assume P is prime

template <int P>

struct ModInt {

using ll = long long;

// assume -P <= x < 2P

private:

int norm(int x) {

if (x < 0)

return x + P;

else if (x >= P)

return x - P;

else

return x;

}

public:

int x;

ModInt(int x = 0) : x(norm(x)) {};

ModInt(ll x) : x(norm(x % P)) {}

int val() const { return x; }

ModInt operator-() const { return ModInt(norm(P - x)); }

ModInt &operator*=(const ModInt &rhs) {

x = ll(x) * rhs.x % P;

return *this;

}

friend ModInt operator*(const ModInt &lhs, const ModInt &rhs) {

ModInt res = lhs;

res *= rhs;

return res;

}

ModInt &operator+=(const ModInt &rhs) {

x = norm(x + rhs.x);

return *this;

}

friend ModInt operator+(const ModInt &lhs, const ModInt &rhs) {

ModInt res = lhs;

res += rhs;

return res;

}

ModInt &operator-=(const ModInt &rhs) {

x = norm(x - rhs.x);

return *this;

}

friend ModInt operator-(const ModInt &lhs, const ModInt &rhs) {

ModInt res = lhs;

res -= rhs;

return res;

}

ModInt power(ll b) const {

ModInt a = x, res = 1;

for (; b; b /= 2, a *= a) {

if (b % 2) res *= a;

}

return res;

}

ModInt inv() const { return power(P - 2); }

ModInt &operator/=(const ModInt &rhs) { return *this *= rhs.inv(); }

friend ModInt operator/(const ModInt &lhs, const ModInt &rhs) {

ModInt res = lhs;

res /= rhs;

return res;

}

friend std::istream &operator>>(std::istream &is, ModInt &a) {

ll v;

is >> v;

a = ModInt(v);

return is;

}

friend std::ostream &operator<<(std::ostream &os, const ModInt &a) {

return os << a.val();

}

};

constexpr int MOD = 998244353, NMAX = 2e5;

using Z = ModInt<MOD>;

int N, K;

Z dp[NMAX][11][4]{};

int main() {

fast_io();

cin >> N >> K;

// we dp on the diff in between elements

dp[0][0][0] = 1LL;

for (int i = 1; i < N; i++) {

// Choose different number

for (int j = 1; j < K; j++) {

dp[i][j][1] = (dp[i - 1][j - 1][0] + dp[i - 1][j - 1][1] +

dp[i - 1][j - 1][3]);

if (j == K - 1)

dp[i][j][1] +=

dp[i - 1][j][0] + dp[i - 1][j][1] + dp[i - 1][j][3];

}

// Dont choose different

for (int j = 0; j < K; j++) {

dp[i][j][0] = dp[i - 1][j][0];

dp[i][j][2] = dp[i - 1][j][1];

dp[i][j][3] = dp[i - 1][j][2] + dp[i - 1][j][3];

}

}

cout << dp[N - 1][K - 1][1] + dp[N - 1][K - 1][2] + dp[N - 1][K - 1][3]

<< '\n';

}

Takeaway

Initially, after I solved this question, I was somewhat unconvinced that not adding $dp_{i-1,j-1,2}$ to $dp_{i,j,1}$ makes sense. However, reading the official editorial shed some light on why this is acceptable. The takeaway here is that for counting problems, it can be beneficial to consider what you might be double-counting and when this double-counting occurs to gain better insight into the overall problem.

Till next time!